|

Edward Snowden

|

|

| Born |

Edward Joseph Snowden

June 21, 1983 (age 36)

|

| Nationality |

American |

| Education |

|

| Occupation |

Computer security consultant |

| Employer |

|

| Known for |

Revealing details of classified United States government surveillance programs |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Awards |

Right Livelihood Award |

| Website |

www.edwardsnowden.com  |

| Signature |

|

Edward Joseph Snowden (born June 21, 1983) is an American whistleblower who copied and leaked highly classified information from the National Security Agency (NSA) in 2013 when he was a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) employee and subcontractor. His disclosures revealed numerous global surveillance programs, many run by the NSA and the Five Eyes Intelligence Alliance with the cooperation of telecommunication companies and European governments, and prompted a cultural discussion about national security and individual privacy.

In 2013, Snowden was hired by an NSA contractor, Booz Allen Hamilton, after previous employment with Dell and the CIA.[1] Snowden says he gradually became disillusioned with the programs with which he was involved and that he tried to raise his ethical concerns through internal channels but was ignored. On May 20, 2013, Snowden flew to Hong Kong after leaving his job at an NSA facility in Hawaii, and in early June he revealed thousands of classified NSA documents to journalists Glenn Greenwald, Laura Poitras, and Ewen MacAskill. Snowden came to international attention after stories based on the material appeared in The Guardian and The Washington Post. Further disclosures were made by other publications including Der Spiegel and The New York Times.

On June 21, 2013, the United States Department of Justice unsealed charges against Snowden of two counts of violating the Espionage Act of 1917 and theft of government property,[2] following which the Department of State revoked his passport.[3] Two days later, he flew into Moscow‘s Sheremetyevo Airport, where Russian authorities noted that his U.S. passport had been cancelled, and he was restricted to the airport terminal for over one month. Russia later granted Snowden the right of asylum with an initial visa for residence for one year, and repeated extensions have permitted him to stay at least until 2020. In early 2016, he became the president of the Freedom of the Press Foundation, a San Francisco-based organization that states its purpose is to protect journalists from hacking and government surveillance.[4] As of 2017 he is married and living in Moscow.[5][6]

On September 17, 2019, his memoir Permanent Record was published.[7] On the first day of publication, the U.S. Department of Justice filed a civil lawsuit against Snowden over publication of his memoir, alleging he had breached nondisclosure agreements signed with the U.S. federal government.[8] Former The Guardian national security reporter Ewen MacAskill called the civil lawsuit a “huge mistake”, noting that the “UK ban of Spycatcher 30 years ago created huge demand”.[9][10] The memoir was listed as no. 1 on Amazon’s bestseller list that same day.[11] In an interview with Amy Goodman on Democracy Now! on September 26, 2019, Snowden clarified he considers himself a “whistleblower” as opposed to a “leaker” as he considers “a leaker only distributes information for personal gain”.[12]

Background

Childhood, family, and education

Edward Joseph Snowden was born on June 21, 1983,[13] in Elizabeth City, North Carolina.[14] His maternal grandfather, Edward J. Barrett,[15][16] a rear admiral in the U.S. Coast Guard, became a senior official with the FBI and was at the Pentagon in 2001 during the September 11 attacks.[17] Snowden’s father, Lonnie, was also an officer in the Coast Guard,[18] and his mother, Elizabeth, is a clerk at the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland.[19][20][21][22][23] His older sister, Jessica, was a lawyer at the Federal Judicial Center in Washington, D.C. Edward Snowden said that he had expected to work for the federal government, as had the rest of his family.[24] His parents divorced in 2001,[25] and his father remarried.[26] Snowden scored above 145 on two separate IQ tests.[24]

In the early 1990s, while still in grade school, Snowden moved with his family to the area of Fort Meade, Maryland.[27] Mononucleosis caused him to miss high school for almost nine months.[24] Rather than returning to school, he passed the GED test[28] and took classes at Anne Arundel Community College.[21] Although Snowden had no undergraduate college degree,[29] he worked online toward a master’s degree at the University of Liverpool, England, in 2011.[30] He was interested in Japanese popular culture, had studied the Japanese language,[31] and worked for an anime company that had a resident office in the U.S.[32][33] He also said he had a basic understanding of Mandarin Chinese and was deeply interested in martial arts. At age 20, he listed Buddhism as his religion on a military recruitment form, noting that the choice of agnostic was “strangely absent.”[34] In September 2019, as part of interviews relating to the release of his memoir Permanent Record, Snowden revealed to The Guardian that he married Lindsay Mills in a courthouse in Moscow.[7]

Political views

Snowden has said that, in the 2008 presidential election, he voted for a third-party candidate, though he “believed in Obama’s promises.” Following the election, he believed President Barack Obama was continuing policies espoused by George W. Bush.[35]

In accounts published in June 2013, interviewers noted that Snowden’s laptop displayed stickers supporting Internet freedom organizations including the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) and the Tor Project.[28] A week after publication of his leaks began, Ars Technica confirmed that Snowden had been an active participant at the site’s online forum from 2001 through May 2012, discussing a variety of topics under the pseudonym “TheTrueHOOHA.”[36] In a January 2009 entry, TheTrueHOOHA exhibited strong support for the U.S. security state apparatus and said leakers of classified information “should be shot in the balls.”[37] However, Snowden disliked Obama’s CIA director appointment of Leon Panetta, saying “Obama just named a fucking politician to run the CIA.”[38] Snowden was also offended by a possible ban on assault weapons, writing “Me and all my lunatic, gun-toting NRA compatriots would be on the steps of Congress before the C-Span feed finished.”[38] Snowden disliked Obama’s economic policies, was against Social Security, and favored Ron Paul‘s call for a return to the gold standard.[38] In 2014, Snowden supported a basic income.[39]

Career

Feeling a duty to fight in the Iraq War to help free oppressed people,[28] Snowden enlisted in the United States Army Reserve on May 7, 2004, and became a Special Forces candidate through its 18X enlistment option.[40] He did not complete the training[13] because he broke both legs in a training accident,[41] and was discharged on September 28, 2004.[42]

Snowden was then employed for less than a year in 2005 as a security guard at the University of Maryland’s Center for Advanced Study of Language, a research center sponsored by the National Security Agency (NSA).[43] According to the University, this is not a classified facility,[44] though it is heavily guarded.[45] In June 2014, Snowden told Wired that his job as a security guard required a high-level security clearance, for which he passed a polygraph exam and underwent a stringent background check.[24]

Employment at CIA

After attending a 2006 job-fair focused on intelligence agencies, Snowden accepted an offer for a position at the CIA.[24][46] The Agency assigned him to the global communications division at CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia.[24]

In May 2006, Snowden wrote in Ars Technica that he had no trouble getting work because he was a “computer wizard”.[34] After distinguishing himself as a junior employee on the top computer team, Snowden was sent to the CIA’s secret school for technology specialists, where he lived in a hotel for six months while studying and training full-time.[24]

In March 2007, the CIA stationed Snowden with diplomatic cover in Geneva, Switzerland, where he was responsible for maintaining computer-network security.[24][47] Assigned to the U.S. Permanent Mission to the United Nations, a diplomatic mission representing U.S. interests before the UN and other international organizations, Snowden received a diplomatic passport and a four-bedroom apartment near Lake Geneva.[24] According to Greenwald, while there Snowden was “considered the top technical and cybersecurity expert” in that country and “was hand-picked by the CIA to support the president at the 2008 NATO summit in Romania”.[48] Snowden described his CIA experience in Geneva as formative, stating that the CIA deliberately got a Swiss banker drunk and encouraged him to drive home. Snowden said that when the latter was arrested, a CIA operative offered to help in exchange for the banker becoming an informant.[49] Ueli Maurer, President of the Swiss Confederation for the year 2013, in June of that year publicly disputed Snowden’s claims. “This would mean that the CIA successfully bribed the Geneva police and judiciary. With all due respect, I just can’t imagine it,” said Maurer.[50] In February 2009, Snowden resigned from the CIA.[51]

NSA sub-contractee as an employee for Dell

In 2009, Snowden began work as a contractee for Dell,[52] which manages computer systems for multiple government agencies. Assigned to an NSA facility at Yokota Air Base near Tokyo, Snowden instructed top officials and military officers on how to defend their networks from Chinese hackers.[24] Snowden looked into Mass surveillance in China prompted him to investigate and then expose Washington’s mass surveillance programme after he was asked in 2009 to brief a conference in Tokyo.[53] During his four years with Dell, he rose from supervising NSA computer system upgrades to working as what his résumé termed a “cyberstrategist” and an “expert in cyber counterintelligence” at several U.S. locations.[54] In 2011, he returned to Maryland, where he spent a year as lead technologist on Dell’s CIA account. In that capacity, he was consulted by the chiefs of the CIA’s technical branches, including the agency’s chief information officer and its chief technology officer.[24] U.S. officials and other sources familiar with the investigation said Snowden began downloading documents describing the government’s electronic spying programs while working for Dell in April 2012.[52] Investigators estimated that of the 50,000 to 200,000 documents Snowden gave to Greenwald and Poitras, most were copied by Snowden while working at Dell.[1]

In March 2012, Dell reassigned Snowden to Hawaii as lead technologist for the NSA’s information-sharing office.[24] At the time of his departure from the U.S. in May 2013, he had been employed for 15 months inside the NSA’s Hawaii regional operations center, which focuses on the electronic monitoring of China and North Korea,[1] the last three of which were with consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton.[55] While intelligence officials have described his position there as a system administrator, Snowden has said he was an infrastructure analyst, which meant that his job was to look for new ways to break into Internet and telephone traffic around the world.[56] On March 15, 2013 – three days after what he later called his “breaking point” of “seeing the Director of National Intelligence, James Clapper, directly lie under oath to Congress”[57] – Snowden quit his job at Dell.[58] Although he has said his career high annual salary was $200,000,[59] Snowden said he took a pay cut to work at Booz Allen,[59] where he sought employment in order to gather data and then release details of the NSA’s worldwide surveillance activity.[60] An anonymous source told Reuters that, while in Hawaii, Snowden may have persuaded 20–25 co-workers to give him their login credentials by telling them he needed them to do his job.[61] The NSA sent a memo to Congress saying that Snowden had tricked a fellow employee into sharing his personal public key infrastructure certificate to gain greater access to the NSA’s computer system.[62][63] Snowden disputed the memo,[64] saying in January 2014, “I never stole any passwords, nor did I trick an army of co-workers.”[65][66] Booz Allen terminated Snowden’s employment on June 10, 2013, one month after he had left the country.[67]

A former NSA co-worker said that although the NSA was full of smart people, Snowden was a “genius among geniuses” who created a widely implemented backup system for the NSA and often pointed out security flaws to the agency. The former colleague said Snowden was given full administrator privileges with virtually unlimited access to NSA data. Snowden was offered a position on the NSA’s elite team of hackers, Tailored Access Operations, but turned it down to join Booz Allen.[64] An anonymous source later said that Booz Allen’s hiring screeners found possible discrepancies in Snowden’s resume but still decided to hire him.[29] Snowden’s résumé stated that he attended computer-related classes at Johns Hopkins University. A spokeswoman for Johns Hopkins said that the university did not find records to show that Snowden attended the university, and suggested that he may instead have attended Advanced Career Technologies, a private for-profit organization that operated as the Computer Career Institute at Johns Hopkins University.[29] The University of Maryland University College acknowledged that Snowden had attended a summer session at a UM campus in Asia. Snowden’s résumé stated that he estimated that he would receive a University of Liverpool computer security master’s degree in 2013. The university said that Snowden registered for an online master’s degree program in computer security in 2011 but was inactive as a student and had not completed the program.[29]

Snowden has said that he had told multiple employees and two supervisors about his concerns, but the NSA disputes his claim.[68] Snowden elaborated in January 2014, saying “[I] made tremendous efforts to report these programs to co-workers, supervisors, and anyone with the proper clearance who would listen. The reactions of those I told about the scale of the constitutional violations ranged from deeply concerned to appalled, but no one was willing to risk their jobs, families, and possibly even freedom to go through what [Thomas Andrews] Drake did.”[66][69] In March 2014, during testimony to the European Parliament, Snowden wrote that before revealing classified information he had reported “clearly problematic programs” to ten officials, who he said did nothing in response.[70] In a May 2014 interview, Snowden told NBC News that after bringing his concerns about the legality of the NSA spying programs to officials, he was told to stay silent on the matter. He asserted that the NSA had copies of emails he sent to their Office of General Counsel, oversight and compliance personnel broaching “concerns about the NSA’s interpretations of its legal authorities. I had raised these complaints not just officially in writing through email, but to my supervisors, to my colleagues, in more than one office.”[17]

In May 2014, U.S. officials released a single email that Snowden had written in April 2013 inquiring about legal authorities but said that they had found no other evidence that Snowden had expressed his concerns to someone in an oversight position.[71] In June 2014, the NSA said it had not been able to find any records of Snowden raising internal complaints about the agency’s operations.[72] That same month, Snowden explained that he himself has not produced the communiqués in question because of the ongoing nature of the dispute, disclosing for the first time that “I am working with the NSA in regard to these records and we’re going back and forth, so I don’t want to reveal everything that will come out.”[73]

In his May 2014 interview with NBC News, Snowden accused the U.S. government of trying to use one position here or there in his career to distract from the totality of his experience, downplaying him as a “low level analyst.” In his words, he was “trained as a spy in the traditional sense of the word in that I lived and worked undercover overseas—pretending to work in a job that I’m not—and even being assigned a name that was not mine.” He said he’d worked for the NSA undercover overseas, and for the DIA had developed sources and methods to keep information and people secure “in the most hostile and dangerous environments around the world. So when they say I’m a low-level systems administrator, that I don’t know what I’m talking about, I’d say it’s somewhat misleading.”[17] In a June interview with Globo TV, Snowden reiterated that he “was actually functioning at a very senior level.”[74] In a July interview with The Guardian, Snowden explained that, during his NSA career, “I began to move from merely overseeing these systems to actively directing their use. Many people don’t understand that I was actually an analyst and I designated individuals and groups for targeting.”[75] Snowden subsequently told Wired that while at Dell in 2011, “I would sit down with the CIO of the CIA, the CTO of the CIA, the chiefs of all the technical branches. They would tell me their hardest technology problems, and it was my job to come up with a way to fix them.”[24]

Of his time as an NSA analyst, directing the work of others, Snowden recalled a moment when he and his colleagues began to have severe ethical doubts. Snowden said 18 to 22-year-old analysts were suddenly

“thrust into a position of extraordinary responsibility, where they now have access to all your private records. In the course of their daily work, they stumble across something that is completely unrelated in any sort of necessary sense—for example, an intimate nude photo of someone in a sexually compromising situation. But they’re extremely attractive. So what do they do? They turn around in their chair and they show a co-worker … and sooner or later this person’s whole life has been seen by all of these other people.”

As Snowden observed it, this behavior happened routinely every two months but was never reported, being considered one of the “fringe benefits” of the work.[76]

Global surveillance disclosures

The exact size of Snowden’s disclosure is unknown,[77] but Australian officials have estimated 15,000 or more Australian intelligence files[78] and British officials estimate at least 58,000 British intelligence files.[79] NSA Director Keith Alexander initially estimated that Snowden had copied anywhere from 50,000 to 200,000 NSA documents.[80] Later estimates provided by U.S. officials were on the order of 1.7 million,[81] a number that originally came from Department of Defense talking points.[82] In July 2014, The Washington Post reported on a cache previously provided by Snowden from domestic NSA operations consisting of “roughly 160,000 intercepted e-mail and instant-message conversations, some of them hundreds of pages long, and 7,900 documents taken from more than 11,000 online accounts.”[83] A U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency report declassified in June 2015 said that Snowden took 900,000 Department of Defense files, more than he downloaded from the NSA.[82]

In March 2014, Army General Martin Dempsey, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told the House Armed Services Committee, “The vast majority of the documents that Snowden … exfiltrated from our highest levels of security … had nothing to do with exposing government oversight of domestic activities. The vast majority of those were related to our military capabilities, operations, tactics, techniques and procedures.”[84] When asked in a May 2014 interview to quantify the number of documents Snowden stole, retired NSA director Keith Alexander said there was no accurate way of counting what he took, but Snowden may have downloaded more than a million documents.[85]

According to Snowden, he did not indiscriminately turn over documents to journalists, stating that “I carefully evaluated every single document I disclosed to ensure that each was legitimately in the public interest. There are all sorts of documents that would have made a big impact that I didn’t turn over”[28] and that “I have to screen everything before releasing it to journalists … If I have time to go through this information, I would like to make it available to journalists in each country.”[60] Despite these measures, the improper redaction of a document by the New York Times resulted in the exposure of intelligence activity against al-Qaeda.[86]

In June 2014, the NSA’s recently installed director, U.S. Navy Admiral Michael S. Rogers, said that while some terrorist groups had altered their communications to avoid surveillance techniques revealed by Snowden, the damage done was not significant enough to conclude that “the sky is falling.”[87] Nevertheless, in February 2015, Rogers said that Snowden’s disclosures had a material impact on the NSA’s detection and evaluation of terrorist activities worldwide.[88]

On June 14, 2015, UK’s Sunday Times reported that Russian and Chinese intelligence services had decrypted more than 1 million classified files in the Snowden cache, forcing the UK’s MI6 intelligence agency to move agents out of live operations in hostile countries. Sir David Omand, a former director of the UK’s GCHQ intelligence gathering agency, described it as a huge strategic setback that was harming Britain, America, and their NATO allies. The Sunday Times said it was not clear whether Russia and China stole Snowden’s data or whether Snowden voluntarily handed it over to remain at liberty in Hong Kong and Moscow.[89][90] In April 2015 the Henry Jackson Society, a British neoconservative think tank, published a report claiming that Snowden’s intelligence leaks negatively impacted Britain’s ability to fight terrorism and organized crime.[91] Gus Hosein, executive director of Privacy International, criticized the report for, in his opinion, presuming that the public became concerned about privacy only after Snowden’s disclosures.[92]

Release of NSA documents

Snowden’s decision to leak NSA documents developed gradually following his March 2007 posting as a technician to the Geneva CIA station.[93] Snowden first made contact with Glenn Greenwald, a journalist working at The Guardian, on December 1, 2012.[94][95] He contacted Greenwald anonymously as “Cincinnatus”[96] and said he had sensitive documents that he would like to share.[97] Greenwald found the measures that the source asked him to take to secure their communications, such as encrypting email, too annoying to employ. Snowden then contacted documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras in January 2013.[98] According to Poitras, Snowden chose to contact her after seeing her New York Times article about NSA whistleblower William Binney.[99] What originally attracted Snowden to both Greenwald and Poitras was a Salon article written by Greenwald detailing how Poitras’s controversial films had made her a target of the government.[97]

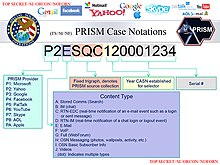

Greenwald began working with Snowden in either February[100] or April 2013, after Poitras asked Greenwald to meet her in New York City, at which point Snowden began providing documents to them.[94] Barton Gellman, writing for The Washington Post, says his first direct contact was on May 16, 2013.[101] According to Gellman, Snowden approached Greenwald after the Post declined to guarantee publication within 72 hours of all 41 PowerPoint slides that Snowden had leaked exposing the PRISM electronic data mining program, and to publish online an encrypted code allowing Snowden to later prove that he was the source.[101]

Snowden communicated using encrypted email,[98] and going by the codename “Verax“. He asked not to be quoted at length for fear of identification by stylometry.[101]

According to Gellman, prior to their first meeting in person, Snowden wrote, “I understand that I will be made to suffer for my actions, and that the return of this information to the public marks my end.”[101] Snowden also told Gellman that until the articles were published, the journalists working with him would also be at mortal risk from the United States Intelligence Community “if they think you are the single point of failure that could stop this disclosure and make them the sole owner of this information.”[101]

In May 2013, Snowden was permitted temporary leave from his position at the NSA in Hawaii, on the pretext of receiving treatment for his epilepsy.[28] In mid-May, Snowden gave an electronic interview to Poitras and Jacob Appelbaum which was published weeks later by Der Spiegel.[102]

After disclosing the copied documents, Snowden promised that nothing would stop subsequent disclosures. In June 2013, he said, “All I can say right now is the US government is not going to be able to cover this up by jailing or murdering me. Truth is coming, and it cannot be stopped.”[103]

Publication

On May 20, 2013, Snowden flew to Hong Kong,[104] where he was staying when the initial articles based on the leaked documents were published,[105] beginning with The Guardian on June 5.[106] Greenwald later said Snowden disclosed 9,000 to 10,000 documents.[107]

Within months, documents had been obtained and published by media outlets worldwide, most notably The Guardian (Britain), Der Spiegel (Germany), The Washington Post and The New York Times (U.S.), O Globo (Brazil), Le Monde (France), and similar outlets in Sweden, Canada, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, and Australia.[108] In 2014, NBC broke its first story based on the leaked documents.[109] In February 2014, for reporting based on Snowden’s leaks, journalists Glenn Greenwald, Laura Poitras, Barton Gellman and The Guardian′s Ewen MacAskill were honored as co-recipients of the 2013 George Polk Award, which they dedicated to Snowden.[110] The NSA reporting by these journalists also earned The Guardian and The Washington Post the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service[111] for exposing the “widespread surveillance” and for helping to spark a “huge public debate about the extent of the government’s spying”. The Guardian‘s chief editor, Alan Rusbridger, credited Snowden for having performed a public service.[112]

Revelations

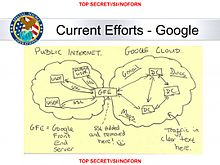

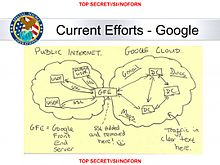

Slide from an NSA presentation on “Google Cloud Exploitation” from its MUSCULAR program;[113] the sketch shows where the “Public Internet” meets the internal “Google Cloud” where user data resides.[114]

The ongoing publication of leaked documents has revealed previously unknown details of a global surveillance apparatus run by the United States’ NSA[115] in close cooperation with three of its four Five Eyes partners: Australia’s ASD,[116] the UK’s GCHQ,[117] and Canada’s CSEC.[118]

On June 5, 2013, media reports documenting the existence and functions of classified surveillance programs and their scope began and continued throughout the entire year. The first program to be revealed was PRISM, which allows for court-approved direct access to Americans’ Google and Yahoo accounts, reported from both The Washington Post and The Guardian published one hour apart.[113][119][120] Barton Gellman of The Washington Post was the first journalist to report on Snowden’s documents. He said the U.S. government urged him not to specify by name which companies were involved, but Gellman decided that to name them “would make it real to Americans.”[121] Reports also revealed details of Tempora, a British black-ops surveillance program run by the NSA’s British partner, GCHQ.[119][122] The initial reports included details about NSA call database, Boundless Informant, and of a secret court order requiring Verizon to hand the NSA millions of Americans’ phone records daily,[123] the surveillance of French citizens’ phone and Internet records, and those of “high-profile individuals from the world of business or politics.”[124][125][126] XKeyscore, an analytical tool that allows for collection of “almost anything done on the internet,” was described by The Guardian as a program that shed light on one of Snowden’s most controversial statements: “I, sitting at my desk [could] wiretap anyone, from you or your accountant, to a federal judge or even the president, if I had a personal email.”[127]

The NSA’s top-secret black budget, obtained from Snowden by The Washington Post, exposed the successes and failures of the 16 spy agencies comprising the U.S. intelligence community,[128] and revealed that the NSA was paying U.S. private tech companies for clandestine access to their communications networks.[129] The agencies were allotted $52 billion for the 2013 fiscal year.[130]

It was revealed that the NSA was harvesting millions of email and instant messaging contact lists,[131] searching email content,[132] tracking and mapping the location of cell phones,[133] undermining attempts at encryption via Bullrun[134][135] and that the agency was using cookies to piggyback on the same tools used by Internet advertisers “to pinpoint targets for government hacking and to bolster surveillance.”[136] The NSA was shown to be secretly accessing Yahoo and Google data centers to collect information from hundreds of millions of account holders worldwide by tapping undersea cables using the MUSCULAR surveillance program.[113][114]

The NSA, the CIA and GCHQ spied on users of Second Life, Xbox Live and World of Warcraft, and attempted to recruit would-be informants from the sites, according to documents revealed in December 2013.[137][138] Leaked documents showed NSA agents also spied on their own “love interests,” a practice NSA employees termed LOVEINT.[139][140] The NSA was shown to be tracking the online sexual activity of people they termed “radicalizers” in order to discredit them.[141] Following the revelation of Black Pearl, a program targeting private networks, the NSA was accused of extending beyond its primary mission of national security. The agency’s intelligence-gathering operations had targeted, among others, oil giant Petrobras, Brazil’s largest company.[142] The NSA and the GCHQ were also shown to be surveilling charities including UNICEF and Médecins du Monde, as well as allies such as European Commissioner Joaquín Almunia and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.[143]

In October 2013, Glenn Greenwald said “the most shocking and significant stories are the ones we are still working on, and have yet to publish.”[144] In November, The Guardian‘s editor-in-chief Alan Rusbridger said that only one percent of the documents had been published.[145] In December, Australia’s Minister for Defence David Johnston said his government assumed the worst was yet to come.[146]

By October 2013, Snowden’s disclosures had created tensions[147][148] between the U.S. and some of its close allies after they revealed that the U.S. had spied on Brazil, France, Mexico,[149] Britain,[150] China,[151] Germany,[152] and Spain,[153] as well as 35 world leaders,[154] most notably German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who said “spying among friends” was unacceptable[155][156] and compared the NSA with the Stasi.[157] Leaked documents published by Der Spiegel in 2014 appeared to show that the NSA had targeted 122 high-ranking leaders.[158]

An NSA mission statement titled “SIGINT Strategy 2012-2016” affirmed that the NSA had plans for continued expansion of surveillance activities. Their stated goal was to “dramatically increase mastery of the global network” and to acquire adversaries’ data from “anyone, anytime, anywhere.”[159] Leaked slides revealed in Greenwald’s book No Place to Hide, released in May 2014, showed that the NSA’s stated objective was to “Collect it All,” “Process it All,” “Exploit it All,” “Partner it All,” “Sniff it All” and “Know it All.”[160]

Snowden said in a January 2014 interview with German television that the NSA does not limit its data collection to national security issues, accusing the agency of conducting industrial espionage. Using the example of German company Siemens, he said, “If there’s information at Siemens that’s beneficial to US national interests—even if it doesn’t have anything to do with national security—then they’ll take that information nevertheless.”[161] In the wake of Snowden’s revelations and in response to an inquiry from the Left Party, Germany’s domestic security agency Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (BfV) investigated and found no concrete evidence that the U.S. conducted economic or industrial espionage in Germany.[162]

In February 2014, during testimony to the European Union, Snowden said of the remaining undisclosed programs, “I will leave the public interest determinations as to which of these may be safely disclosed to responsible journalists in coordination with government stakeholders.”[163]

In March 2014, documents disclosed by Glenn Greenwald writing for The Intercept showed the NSA, in cooperation with the GCHQ, has plans to infect millions of computers with malware using a program called TURBINE.[164] Revelations included information about QUANTUMHAND, a program through which the NSA set up a fake Facebook server to intercept connections.[164]

According to a report in The Washington Post in July 2014, relying on information furnished by Snowden, 90% of those placed under surveillance in the U.S. are ordinary Americans, and are not the intended targets. The newspaper said it had examined documents including emails, message texts, and online accounts, that support the claim.[165]

In an August 2014 interview, Snowden for the first time disclosed a cyberwarfare program in the works, codenamed MonsterMind, that would automate detection of a foreign cyberattack as it began and automatically fire back. “These attacks can be spoofed,” said Snowden. “You could have someone sitting in China, for example, making it appear that one of these attacks is originating in Russia. And then we end up shooting back at a Russian hospital. What happens next?”[24]

Motivations

Snowden speaks about the NSA leaks, in Hong Kong, filmed by Laura Poitras.

Snowden first contemplated leaking confidential documents around 2008 but held back, partly because he believed the newly elected Barack Obama might introduce reforms.[1] After the disclosures, his identity was made public by The Guardian at his request on June 9, 2013.[100] “I do not want to live in a world where everything I do and say is recorded,” he said. “My sole motive is to inform the public as to that which is done in their name and that which is done against them.”[104]

Snowden said he wanted to “embolden others to step forward” by demonstrating that “they can win.”[101] He also said that the system for reporting problems did not work. “You have to report wrongdoing to those most responsible for it.” He cited a lack of whistleblower protection for government contractors, the use of the Espionage Act of 1917 to prosecute leakers, and his belief that had he used internal mechanisms to “sound the alarm,” his revelations “would have been buried forever.”[93][166]

In December 2013, upon learning that a U.S. federal judge had ruled the collection of U.S. phone metadata conducted by the NSA as likely unconstitutional, Snowden said, “I acted on my belief that the NSA’s mass surveillance programs would not withstand a constitutional challenge, and that the American public deserved a chance to see these issues determined by open courts … today, a secret program authorized by a secret court was, when exposed to the light of day, found to violate Americans’ rights.”[167]

In January 2014, Snowden said his “breaking point” was “seeing the Director of National Intelligence, James Clapper, directly lie under oath to Congress.”[57] This referred to testimony on March 12, 2013—three months after Snowden first sought to share thousands of NSA documents with Greenwald,[94] and nine months after the NSA says Snowden made his first illegal downloads during the summer of 2012[1]—in which Clapper denied to the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence that the NSA wittingly collects data on millions of Americans.[168] Snowden said, “There’s no saving an intelligence community that believes it can lie to the public and the legislators who need to be able to trust it and regulate its actions. Seeing that really meant for me there was no going back. Beyond that, it was the creeping realization that no one else was going to do this. The public had a right to know about these programs.”[169] In March 2014, Snowden said he had reported policy or legal issues related to spying programs to more than ten officials, but as a contractor had no legal avenue to pursue further whistleblowing.[70]

Flight from the United States

Hong Kong

In May 2013, Snowden took a leave of absence, telling his supervisors he was returning to the mainland for epilepsy treatment, but instead left Hawaii for Hong Kong[170] where he arrived on May 20. Snowden told Guardian reporters in June that he had been in his room at the Mira Hotel since his arrival in the city, rarely going out. On June 10, correspondent Ewen MacAskill said Snowden had left his hotel only briefly three times since May 20.[171]

Hong Kong rally to support Snowden, June 15, 2013

Snowden vowed to challenge any extradition attempt by the U.S. government, and engaged a Hong Kong-based Canadian human rights lawyer Robert Tibbo as a legal adviser.[1][172][173] Snowden told the South China Morning Post that he planned to remain in Hong Kong for as long as its government would permit.[174][175] Snowden also told the Post that “the United States government has committed a tremendous number of crimes against Hong Kong [and] the PRC as well,”[176] going on to identify Chinese Internet Protocol addresses that the NSA monitored and stating that the NSA collected text-message data for Hong Kong residents. Glenn Greenwald said Snowden was motivated by a need to “ingratiate himself to the people of Hong Kong and China.”[177]

After leaving the Mira Hotel, Snowden was housed for two weeks in a number of apartments by other refugees seeking asylum in Hong Kong, an arrangement set up by Tibbo to hide from the US authorities.[178][179] The Russian newspaper Kommersant nevertheless reported that Snowden was living at the Russian consulate shortly before his departure from Hong Kong to Moscow.[180] Ben Wizner, a lawyer with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and legal adviser to Snowden, said in January 2014, “Every news organization in the world has been trying to confirm that story. They haven’t been able to, because it’s false.”[181] Likewise rejecting the Kommersant story was Anatoly Kucherena, who became Snowden’s lawyer in July 2013 when Snowden asked him for help in seeking temporary asylum in Russia.[182] Kucherena said Snowden did not communicate with Russian diplomats while he was in Hong Kong.[183][184] In early September 2013, however, Russian president Vladimir Putin said that, a few days before boarding a plane to Moscow, Snowden met in Hong Kong with Russian diplomatic representatives.[185]

On June 22, 18 days after publication of Snowden’s NSA documents began, officials revoked his U.S. passport.[186] On June 23, Snowden boarded the commercial Aeroflot flight SU213 to Moscow, accompanied by Sarah Harrison of WikiLeaks.[187][188] Hong Kong authorities said that Snowden had not been detained for the U.S. because the request had not fully complied with Hong Kong law,[189][190] and there was no legal basis to prevent Snowden from leaving.[191][192][Notes 1] On June 24, a U.S. State Department spokesman rejected the explanation of technical noncompliance, accusing the Hong Kong government of deliberately releasing a fugitive despite a valid arrest warrant and after having sufficient time to prohibit his travel.[195] That same day, Julian Assange said that WikiLeaks had paid for Snowden’s lodging in Hong Kong and his flight out.[196]

In October 2013, Snowden said that before flying to Moscow, he gave all the classified documents he had obtained to journalists he met in Hong Kong, and kept no copies for himself.[93] In January 2014, he told a German TV interviewer that he gave all of his information to American journalists reporting on American issues.[57] During his first American TV interview, in May 2014, Snowden said he had protected himself from Russian leverage by destroying the material he had been holding before landing in Moscow.[17]

In January 2019, Vanessa Rodel, one of the refugees who had housed Snowden in Hong Kong, and her 7-year-old daughter were granted asylum by Canada. Five other people who helped Snowden still remain in Hong Kong awaiting a response to their asylum request.[197]

Russia

On June 23, 2013, Snowden landed at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport.[198] WikiLeaks said he was on a circuitous but safe route to asylum in Ecuador.[199] Snowden had a seat reserved to continue to Cuba[200] but did not board that onward flight, saying in a January 2014 interview that he intended to transit through Russia but was stopped en route. He asserted “a planeload of reporters documented the seat I was supposed to be in” when he was ticketed for Havana, but the U.S. cancelled his passport.[181] He said the U.S. wanted him to stay in Moscow so “they could say, ‘He’s a Russian spy.'”[74] Greenwald’s account differed on the point of Snowden being already ticketed. According to Greenwald, Snowden’s passport was valid when he departed Hong Kong but was revoked during the hours he was in transit to Moscow, preventing him from obtaining a ticket to leave Russia. Greenwald said Snowden was thus forced to stay in Moscow and seek asylum.[201]

According to one Russian report, Snowden planned to fly from Moscow through Havana to Latin America; however, Cuba told Moscow it would not allow the Aeroflot plane carrying Snowden to land.[183] Russian newspaper Kommersant reported that Cuba had a change of heart after receiving pressure from U.S. officials,[202] leaving him stuck in the transit zone because at the last minute Havana told officials in Moscow not to allow him on the flight.[203] The Washington Post contrasted this version with what it called “widespread speculation” that Russia never intended to let Snowden proceed.[204] Fidel Castro called claims that Cuba would have blocked Snowden’s entry a “lie” and a “libel.”[200] Describing Snowden’s arrival in Moscow as a surprise and likening it to “an unwanted Christmas gift,”[205] Russian president Putin said that Snowden remained in the transit area of Sheremetyevo Airport, had committed no crime in Russia, was free to leave and should do so.[206] Putin denied that Russia’s intelligence agencies had worked or were working with Snowden.[205]

Following Snowden’s arrival in Moscow, the White House expressed disappointment in Hong Kong’s decision to allow him to leave.[207][208][195] An anonymous U.S. official not authorized to discuss the matter told AP Snowden’s passport had been revoked before he left Hong Kong, but that a senior official in a country or airline could order subordinates to overlook the withdrawn passport.[209] U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry said that Snowden’s passport was cancelled “within two hours” of the charges against Snowden being made public[3] which was Friday, June 21.[2] In a July 1 statement, Snowden said, “Although I am convicted of nothing, [the U.S. government] has unilaterally revoked my passport, leaving me a stateless person. Without any judicial order, the administration now seeks to stop me exercising a basic right. A right that belongs to everybody. The right to seek asylum.”[210]

Four countries offered Snowden permanent asylum: Ecuador, Nicaragua, Bolivia, and Venezuela.[211] No direct flights between Moscow and Venezuela, Bolivia or Nicaragua existed, however, and the U.S. pressured countries along his route to hand him over. Snowden said in July 2013 that he decided to bid for asylum in Russia because he felt there was no safe way to reach Latin America.[212] Snowden said he remained in Russia because “when we were talking about possibilities for asylum in Latin America, the United States forced down the Bolivian President’s plane”, citing the Morales plane incident. On the issue, he said “some governments in Western European and North American states have demonstrated a willingness to act outside the law, and this behavior persists today. This unlawful threat makes it impossible for me to travel to Latin America and enjoy the asylum granted there in accordance with our shared rights.”[213] He said that he would travel from Russia if there was no interference from the U.S. government.[181]

Four months after Snowden received asylum in Russia, Julian Assange commented, “While Venezuela and Ecuador could protect him in the short term, over the long term there could be a change in government. In Russia, he’s safe, he’s well-regarded, and that is not likely to change. That was my advice to Snowden, that he would be physically safest in Russia.”[170] According to Snowden, “the CIA has a very powerful presence [in Latin America] and the governments and the security services there are relatively much less capable than, say, Russia…. they could have basically snatched me….”[214]

In an October 2014 interview with The Nation magazine, Snowden reiterated that he had originally intended to travel to Latin America: “A lot of people are still unaware that I never intended to end up in Russia.” According to Snowden, the U.S. government “waited until I departed Hong Kong to cancel my passport in order to trap me in Russia.” Snowden added, “If they really wanted to capture me, they would’ve allowed me to travel to Latin America, because the CIA can operate with impunity down there. They did not want that; they chose to keep me in Russia.”[215]

Morales plane incident

Spain, France, and Italy (red) denied Bolivian president Evo Morales permission to cross their airspace. Morales’s plane landed in Austria (yellow).

On July 1, 2013, president Evo Morales of Bolivia, who had been attending a conference in Russia, suggested during an interview with Russia Today that he would consider a request by Snowden for asylum.[216] The following day, Morales’s plane, en route to Bolivia, was rerouted to Austria and landed there, after France, Spain, and Italy denied access to their airspace. While the plane was parked in Vienna, the Spanish ambassador to Austria arrived with two embassy personnel and asked to search the plane but they were denied permission by Morales himself.[217] U.S. officials had raised suspicions that Snowden may have been on board.[218] Morales blamed the U.S. for putting pressure on European countries, and said that the grounding of his plane was a violation of international law.[219]

In April 2015, Bolivia’s ambassador to Russia, María Luisa Ramos Urzagaste, accused Julian Assange of inadvertently putting Morales’s life at risk by intentionally providing to the U.S. false rumors that Snowden was on Morales’s plane. Assange responded that “we weren’t expecting this outcome. The result was caused by the United States’ intervention. We can only regret what happened.”[220][221]

Asylum applications

Snowden applied for political asylum to 21 countries.[222][223] A statement attributed to him contended that the U.S. administration, and specifically Vice President Joe Biden, had pressured the governments to refuse his asylum petitions. Biden had telephoned President Rafael Correa days prior to Snowden’s remarks, asking the Ecuadorian leader not to grant Snowden asylum.[224] Ecuador had initially offered Snowden a temporary travel document but later withdrew it,[225] and Correa later called the offer a mistake.[226]

In a July 1 statement published by WikiLeaks, Snowden accused the U.S. government of “using citizenship as a weapon” and using what he described as “old, bad tools of political aggression.” Citing Obama’s promise to not allow “wheeling and dealing” over the case, Snowden commented, “This kind of deception from a world leader is not justice, and neither is the extralegal penalty of exile.”[227] Several days later, WikiLeaks announced that Snowden had applied for asylum in six additional countries, but declined to name them, alleging attempted U.S. interference.[228]

After evaluating the law and Snowden’s situation, the French interior ministry rejected his request for asylum.[229] Poland refused to process his application because it did not conform to legal procedure.[230] Brazil’s Foreign Ministry said the government planned no response to Snowden’s asylum request. Germany and India rejected Snowden’s application outright, while Austria, Ecuador, Finland, Norway, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain said he must be on their territory to apply.[231][232][233] In November 2014, Germany announced that Snowden had not renewed his previously denied request and was not being considered for asylum.[234] Glenn Greenwald later reported that Sigmar Gabriel, Vice-Chancellor of Germany, told him the U.S. government had threatened to stop sharing intelligence if Germany offered Snowden asylum or arranged for his travel there.[235]

Putin said on July 1, 2013, that if Snowden wanted to be granted asylum in Russia, he would be required to “stop his work aimed at harming our American partners.”[236] A spokesman for Putin subsequently said that Snowden had withdrawn his asylum application upon learning of the conditions.[237]

In a July 12 meeting at Sheremetyevo Airport with representatives of human rights organizations and lawyers, organized in part by the Russian government,[238] Snowden said he was accepting all offers of asylum that he had already received or would receive. He added that Venezuela’s grant of asylum formalized his asylee status, removing any basis for state interference with his right to asylum.[239] He also said he would request asylum in Russia until he resolved his travel problems.[240] Russian Federal Migration Service officials confirmed on July 16 that Snowden had submitted an application for temporary asylum.[241] On July 24, Kucherena said his client wanted to find work in Russia, travel and create a life for himself, and had already begun learning Russian.[242]

Amid media reports in early July 2013 attributed to U.S. administration sources that Obama’s one-on-one meeting with Putin, ahead of a G20 meeting in St Petersburg scheduled for September, was in doubt due to Snowden’s protracted sojourn in Russia,[243] top U.S. officials repeatedly made it clear to Moscow that Snowden should immediately be returned to the United States to face charges for the unauthorized leaking of classified information.[244][245][246] His Russian lawyer said Snowden needed asylum because he faced persecution by the U.S. government and feared “that he could be subjected to torture and capital punishment.”[247]

In a letter to Russian Minister of Justice Aleksandr Konovalov dated July 23, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder repudiated Snowden’s claim to refugee status, and offered a limited validity passport good for direct return to the U.S.[248] He further asserted that Snowden would not be subject to torture or the death penalty, and would receive trial in a civilian court with proper legal counsel.[249] The same day, the Russian president’s spokesman reiterated that his government would not hand over Snowden, noting that Putin was not personally involved in the matter and that it was being handled through talks between the FBI and Russia’s FSB.[250]

Criminal charges

On June 14, 2013, United States federal prosecutors filed a criminal complaint against Snowden, charging him with theft of government property and two counts of violating the Espionage Act of 1917 through unauthorized communication of national defense information and willful communication of classified communications intelligence information to an unauthorized person.[2][248] Each of the three charges carries a maximum possible prison term of ten years. The charge was initially secret and was unsealed a week later.

Snowden was asked in a January 2014 interview about returning to the U.S. to face the charges in court, as Obama had suggested a few days prior. Snowden explained why he rejected the request:

What he doesn’t say are that the crimes that he’s charged me with are crimes that don’t allow me to make my case. They don’t allow me to defend myself in an open court to the public and convince a jury that what I did was to their benefit. … So it’s, I would say, illustrative that the President would choose to say someone should face the music when he knows the music is a show trial.[57][251]

Snowden’s legal representative, Jesselyn Radack, wrote that “the Espionage Act effectively hinders a person from defending himself before a jury in an open court.” She said that the “arcane World War I law” was never meant to prosecute whistleblowers, but rather spies who betrayed their trust by selling secrets to enemies for profit. Non-profit betrayals were not considered.[252]

Civil lawsuit

On September 17, 2019, the United States filed a lawsuit against Snowden for alleged violations of non-disclosure agreements with the CIA and NSA.[253] The complaint alleges that Snowden violated prepublication obligations related to the publication of his memoir Permanent Record. The complaint lists the publishers Macmillan and Holtzbrink as relief-defendants.[254]

Asylum in Russia

On June 23, 2013, Snowden landed at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport aboard a commercial Aeroflot flight from Hong Kong.[255][187][256] On August 1, after 39 days in the transit section, he left the airport and was granted temporary asylum in Russia for one year.[257] A year later, his temporary asylum having expired, Snowden received a three-year residency permit allowing him to travel freely within Russia and to go abroad for up to three months. He was not granted permanent political asylum.[258] In January 2017, a spokesperson for the Russian foreign ministry wrote on Facebook that Snowden’s asylum, which was due to expire in 2017, was extended by “a couple more years”.[259][260] Snowden’s lawyer Anatoly Kucherena said the extension was valid until 2020.[261]

As of October 2019, Snowden had been granted permanent residency in Russia, which is renewed every three years. He secretly married Lindsay Mills in 2017. By 2019 he no longer felt the need to be disguised in public and lived what was described as a “more or less normal life”, able to travel around Russia and make a living from speaking arrangements (locally and over the internet). His memoir Permanent Record was released internationally, and while U.S. royalties were expected to be seized, he was able to receive the advance.[6] According to Snowden, “One of the things that is lost in all the problematic politics of the Russian government is the fact this is one of the most beautiful countries in the world” with “friendly” and “warm” people.[6] In another interview, Snowden went on to say: “There’s a way to criticize the Russian government’s policies without criticizing the Russian people who are ordinary people, who just want to have a happy life; they just want to do better. They want the same things that you do.”[262]

Reaction

United States

A subject of controversy, Snowden has been variously called a hero,[263][264][265] a whistleblower,[266][267][268][269] a dissident,[270] a patriot,[271][272][273] and a traitor.[274][275][276][277] Pentagon Papers leaker Daniel Ellsberg called Snowden’s release of NSA material the most significant leak in U.S. history.[278][279]

Government officials

Numerous high-ranking current or former U.S. government officials reacted publicly to Snowden’s disclosures.

- 2013

- Director of National Intelligence James Clapper condemned the leaks as doing “huge, grave damage” to U.S. intelligence capabilities.[280] Ex-CIA director James Woolsey said that if Snowden were convicted of treason, he should be hanged.[281]

- FBI director Robert Mueller said that the U.S. government is “taking all necessary steps to hold Edward Snowden responsible for these disclosures.”[282]

- 2014

- House Intelligence Committee chairman Mike Rogers and ranking member Dutch Ruppersberger said a classified Pentagon report written by military intelligence officials contended that Snowden’s leaks had put U.S. troops at risk and prompted terrorists to change their tactics, and that most files copied were related to current U.S. military operations.[283]

-

- President Barack Obama said that “our nation’s defense depends in part on the fidelity of those entrusted with our nation’s secrets. If any individual who objects to government policy can take it into their own hands to publicly disclose classified information, then we will not be able to keep our people safe, or conduct foreign policy.” Obama also objected to the “sensational” way the leaks had been reported, saying the reporting often “shed more heat than light.” He went on to assert that the disclosures had revealed “methods to our adversaries that could impact our operations.”[284]

-

- Former congressman Ron Paul began a petition urging the Obama Administration to grant Snowden clemency.[285] Paul released a video on his website saying, “Edward Snowden sacrificed his livelihood, citizenship, and freedom by exposing the disturbing scope of the NSA’s worldwide spying program. Thanks to one man’s courageous actions, Americans know about the truly egregious ways their government is spying on them.”[286]

-

- Mike McConnell—former NSA director and current vice chairman at Booz Allen Hamilton—said that Snowden was motivated by revenge when the NSA did not offer him the job he wanted. “At this point,” said McConnell, “he being narcissistic and having failed at most everything he did, he decides now I’m going to turn on them.”[287]

-

- Former president Jimmy Carter said that if he were still president today he would “certainly consider” giving Snowden a pardon were he to be found guilty and imprisoned for his leaks.[288]

-

- Former secretary of state Hillary Clinton said, “[W]e have all these protections for whistleblowers. If [Snowden] were concerned and wanted to be part of the American debate…it struck me as…sort of odd that he would flee to China, because Hong Kong is controlled by China, and that he would then go to Russia—two countries with which we have very difficult cyberrelationships.” As Clinton saw it, “turning over a lot of that material—intentionally or unintentionally—drained, gave all kinds of information, not only to big countries, but to networks and terrorist groups and the like. So I have a hard time thinking that somebody who is a champion of privacy and liberty has taken refuge in Russia, under Putin’s authority.”[289] Clinton later said that if Snowden wished to return to the U.S., “knowing he would be held accountable,” he would have the right “to launch both a legal defense and a public defense, which can of course affect the legal defense.”[290]

-

- Secretary of State John Kerry said Snowden had “damaged his country very significantly” and “hurt operational security” by telling terrorists how to evade detection. “The bottom line,” Kerry added, “is this man has betrayed his country, sitting in Russia where he has taken refuge. You know, he should man up and come back to the United States.”[291]

-

- Former vice president Al Gore said Snowden “clearly violated the law so you can’t say OK, what he did is all right. It’s not. But what he revealed in the course of violating important laws included violations of the U.S. constitution that were way more serious than the crimes he committed. In the course of violating important law, he also provided an important service. … Because we did need to know how far this has gone.”[292]

-

- In December, President Obama nominated former deputy defense secretary Ashton Carter to succeed outgoing Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel. Seven months before, Carter had said, “We had a cyber Pearl Harbor. His name was Edward Snowden.” Carter charged that U.S. security officials “screwed up spectacularly in the case of Snowden. And this knucklehead had access to destructive power that was much more than any individual person should have access to.”[293]

Debate

In the U.S., Snowden’s actions precipitated an intense debate on privacy and warrantless domestic surveillance.[294][295] President Obama was initially dismissive of Snowden, saying “I’m not going to be scrambling jets to get a 29-year-old hacker.”[296][297][298] In August 2013, Obama rejected the suggestion that Snowden was a patriot,[299] and in November said that “the benefit of the debate he generated was not worth the damage done, because there was another way of doing it.”[300]

In June 2013, U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont shared a “must read” news story on his blog by Ron Fournier, stating “Love him or hate him, we all owe Snowden our thanks for forcing upon the nation an important debate. But the debate shouldn’t be about him. It should be about the gnawing questions his actions raised from the shadows.”[301] In 2015, Sanders stated that “Snowden played a very important role in educating the American public” and that although Snowden should not go unpunished for breaking the law, “that education should be taken into consideration before the sentencing.”[302]

Snowden said in December 2013 that he was “inspired by the global debate” ignited by the leaks and that NSA’s “culture of indiscriminate global espionage … is collapsing.”[303]

At the end of 2013, however, The Washington Post noted that the public debate and its offshoots had produced no meaningful change in policy, with the status quo continuing.[139]

In 2016, on The Axe Files podcast, former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder said that Snowden “performed a public service by raising the debate that we engaged in and by the changes that we made.” Holder nevertheless said that Snowden’s actions were inappropriate and illegal.[304]

In September 2016, the bipartisan U.S. House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence completed a review of the Snowden disclosures and said that the federal government would have to spend millions of dollars responding to the fallout from Snowden’s disclosures.[305] The report also said that “the public narrative popularized by Snowden and his allies is rife with falsehoods, exaggerations, and crucial omissions.”[306] The report was denounced by Washington Post reporter Barton Gellman, who called it “aggressively dishonest” and “contemptuous of fact.”[307]

Presidential panel

In August 2013, President Obama said that he had called for a review of U.S. surveillance activities before Snowden had begun revealing details of the NSA’s operations,[299] and announced that he was directing DNI James Clapper “to establish a review group on intelligence and communications technologies.”[308][309] In December, the task force issued 46 recommendations that, if adopted, would subject the NSA to additional scrutiny by the courts, Congress, and the president, and would strip the NSA of the authority to infiltrate American computer systems using backdoors in hardware or software.[310] Panel member Geoffrey R. Stone said there was no evidence that the bulk collection of phone data had stopped any terror attacks.[311]

Court rulings

On June 6, 2013, in the wake of Snowden’s leaks, conservative public interest lawyer and Judicial Watch founder Larry Klayman filed a lawsuit claiming that the federal government had unlawfully collected metadata for his telephone calls and was harassing him. In Klayman v. Obama, Judge Richard J. Leon referred to the NSA’s “almost-Orwellian technology” and ruled the bulk telephone metadata program to be probably unconstitutional.[312] Snowden later described Judge Leon’s decision as vindication.[313]

On June 11, the ACLU filed a lawsuit against James Clapper, Director of National Intelligence, alleging that the NSA’s phone records program was unconstitutional. In December 2013, ten days after Judge Leon’s ruling, Judge William H. Pauley III came to the opposite conclusion. In ACLU v. Clapper, although acknowledging that privacy concerns are not trivial, Pauley found that the potential benefits of surveillance outweigh these considerations and ruled that the NSA’s collection of phone data is legal.[314]

Gary Schmitt, former staff director of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, wrote that “The two decisions have generated public confusion over the constitutionality of the NSA’s data collection program—a kind of judicial ‘he-said, she-said’ standoff.”[315]

On May 7, 2015, in the case of ACLU v. Clapper, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit said that Section 215 of the Patriot Act did not authorize the NSA to collect Americans’ calling records in bulk, as exposed by Snowden in 2013. The decision voided U.S. District Judge William Pauley’s December 2013 finding that the NSA program was lawful, and remanded the case to him for further review. The appeals court did not rule on the constitutionality of the bulk surveillance, and declined to enjoin the program, noting the pending expiration of relevant parts of the Patriot Act. Circuit Judge Gerard E. Lynch wrote that, given the national security interests at stake, it was prudent to give Congress an opportunity to debate and decide the matter.[316]

USA Freedom Act

On June 2, 2015, the U.S. Senate passed, and President Obama signed, the USA Freedom Act which restored in modified form several provisions of the Patriot Act that had expired the day before, while for the first time imposing some limits on the bulk collection of telecommunication data on U.S. citizens by American intelligence agencies. The new restrictions were widely seen as stemming from Snowden’s revelations.[317][318]

Europe

Hans-Georg Maaßen, head of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution, Germany’s domestic security agency, speculated that Snowden could have been working for the Russian government.[319][320] Snowden rejected this insinuation,[321] speculating on Twitter in German that “it cannot be proven if Maaßen is an agent of the SVR or FSB.”[322]

Crediting the Snowden leaks, the United Nations General Assembly unanimously adopted Resolution 68/167 in December 2013. The non-binding resolution denounced unwarranted digital surveillance and included a symbolic declaration of the right of all individuals to online privacy.[323][324][325]

Support for Snowden came from Latin American leaders including the Argentinian President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff, Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa, Bolivian President Evo Morales, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, and Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega.[326][327]

In an official report published in October 2015, the United Nations special rapporteur for the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of speech, Professor David Kaye, criticized the U.S. government’s harsh treatment of, and bringing criminal charges against, whistleblowers, including Edward Snowden. The report found that Snowden’s revelations were important for people everywhere and made “a deep and lasting impact on law, policy and politics.”[328][329] The European Parliament invited Snowden to make a pre-recorded video appearance to aid their NSA investigation.[330][331] Snowden gave written testimony in which he said that he was seeking asylum in the EU, but that he was told by European Parliamentarians that the U.S. would not allow EU partners to make such an offer.[332] He told the Parliament that the NSA was working with the security agencies of EU states to “get access to as much data of EU citizens as possible.”[333] The NSA’s Foreign Affairs Division, he claimed, lobbies the EU and other countries to change their laws, allowing for “everyone in the country” to be spied on legally.[334]

In July 2014, Navi Pillay, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, told a news conference in Geneva that the U.S. should abandon its efforts to prosecute Snowden, since his leaks were in the public interest.[335]

Public opinion polls

A rally in Germany in support of Snowden on August 30, 2014

Surveys conducted by news outlets and professional polling organizations found that American public opinion was divided on Snowden’s disclosures, and that those polled in Canada and Europe were more supportive of Snowden than respondents in the U.S. although more Americans have grown more supportive of Snowden’s disclosure. In Germany, Italy, France, the Netherlands and Spain more than 80% of people familiar with Snowden view him positively.[336]

Recognition

For his global surveillance disclosures, Snowden has been honored by publications and organizations based in Europe and the United States. He was voted as The Guardian‘s person of the year 2013, garnering four times the number of votes as any other candidate.[337]

Teleconference speaking engagements

In March 2014, Snowden spoke at the South by Southwest (SXSW) Interactive technology conference in Austin, Texas, in front of 3,500 attendees. He participated by teleconference carried over multiple routers running the Google Hangouts platform. On-stage moderators were Christopher Soghoian and Snowden’s legal counsel Wizner, both from the ACLU.[338] Snowden said that the NSA was “setting fire to the future of the internet,” and that the SXSW audience was “the firefighters.”[339][340][341] Attendees could use Twitter to send questions to Snowden, who answered one by saying that information gathered by corporations was much less dangerous than that gathered by a government agency, because “governments have the power to deprive you of your rights.”[339] Representative Mike Pompeo (R-KS) of the House Intelligence Committee, and later director of the CIA, had tried unsuccessfully to get the SXSW management to cancel Snowden’s appearance; instead, SXSW director Hugh Forrest said that the NSA was welcome to respond to Snowden at the 2015 conference.[339]

Speaking via telepresence robot, Snowden addresses the TED conference from Russia.

Later that month, Snowden appeared by teleconference at the TED conference in Vancouver, British Columbia. Represented on stage by a robot with a video screen, video camera, microphones and speakers, Snowden conversed with TED curator Chris Anderson, and told the attendees that online businesses should act quickly to encrypt their websites. He described the NSA’s PRISM program as the U.S. government using businesses to collect data for them, and that the NSA “intentionally misleads corporate partners” using, as an example, the Bullrun decryption program to create backdoor access.[342] Snowden said he would gladly return to the U.S. if given immunity from prosecution, but that he was more concerned about alerting the public about abuses of government authority.[342] Anderson invited Internet pioneer Tim Berners-Lee on stage to converse with Snowden, who said that he would support Berners-Lee’s concept of an “internet Magna Carta” to “encode our values in the structure of the internet.”[342][343]

On September 15, 2014, Snowden appeared via remote video link, along with Julian Assange, on Kim Dotcom’s Moment of Truth town hall meeting held in Auckland.[344] He made a similar video link appearance on February 2, 2015, along with Greenwald, as the keynote speaker at the World Affairs Conference at Upper Canada College in Toronto.[345]

In March 2015, while speaking at the FIFDH (international human rights film festival) he made a public appeal for Switzerland to grant him asylum, saying he would like to return to live in Geneva, where he once worked undercover for the Central Intelligence Agency.[346]

In April 2015, John Oliver, the host of Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, flew to Moscow to Interview Edward Snowden.[347]

On November 10, 2015, Snowden appeared at the Newseum, via remote video link, for PEN American Center’s “Secret Sources: Whistleblowers, National Security and Free Expression,” event.[348]

In 2015, Snowden earned over $200,000 from digital speaking engagements in the U.S.[349]

On March 19, 2016, Snowden delivered the opening keynote address of the LibrePlanet conference, a meeting of international free software activists and developers presented by the Free Software Foundation. The conference was held at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and was the first such time Snowden spoke via teleconference using a full free software stack, end-to-end.[jargon][350][351][352][353]

On July 21, 2016, Snowden and hardware hacker Bunnie Huang, in a talk at MIT Media Lab‘s Forbidden Research event, published research for a smartphone case, the so-called Introspection Engine, that would monitor signals received and sent by that phone to provide an alert to the user if his or her phone is transmitting or receiving information when it shouldn’t be (for example when it’s turned off or in airplane mode), a feature described by Snowden to be useful for journalists or activists operating under hostile governments that would otherwise track their activities through their phones.[354][355][356][357][358]

The “Snowden effect”

In July 2013, media critic Jay Rosen defined The Snowden Effect as “Direct and indirect gains in public knowledge from the cascade of events and further reporting that followed Edward Snowden’s leaks of classified information about the surveillance state in the U.S.”[359] In December 2013, The Nation wrote that Snowden had sparked an overdue debate about national security and individual privacy.[360] In Forbes, the effect was seen to have nearly united the U.S. Congress in opposition to the massive post-9/11 domestic intelligence gathering system.[361] In its Spring 2014 Global Attitudes Survey, the Pew Research Center found that Snowden’s disclosures had tarnished the image of the United States, especially in Europe and Latin America.[362]

Jewel v. NSA

On November 2, 2018, Snowden provided a court declaration in Jewel v. National Security Agency.[363][364][365]

Bibliography

In popular culture

Snowden’s impact as a public figure has been felt in cinema,[368] television,[369] advertising,[370] video games,[371][372] literature,[373][374] music,[375][376][377] statuary,[378][379] and social media.

Snowden gave Channel 4’s “Alternative Christmas Message” in December 2013.[6]

The film Snowden, based on Snowden’s leaking of classified US government material, was released in 2016.[382] The documentary Citizenfour won Best Documentary Feature at the 87th Academy Awards.[383]

See also

Notes

- ^ Hong Kong’s Secretary for Justice Rimsky Yuen argued that government officials did not issue a provisional arrest warrant for Snowden due to “discrepancies and missing information” in the paperwork sent by U.S. authorities. Yuen explained that Snowden’s full name was inconsistent, and his U.S. passport number was also missing.[193] Hong Kong also wanted more details of the charges and evidence against Snowden to make sure it was not a political case. Yuen said he spoke to U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder by phone to reinforce the request for details “absolutely necessary” for detention of Snowden. Yuen said “As the US government had failed to provide the information by the time Snowden left Hong Kong, it was impossible for the Department of Justice to apply to a court for a temporary warrant of arrest. In fact, even at this time, the US government has still not provided the details we asked for.”[194]

[I do not include the (383) References, or the suggestions for Further Reading, or the External Links

]